In the annals of history, artifacts and monuments serve as silent narrators, telling tales of civilizations long vanished. Among these narrators are two statues, standing worlds apart, yet bound by an invisible thread of mystery. The story of Ninurta, a Sumerian deity, unfolds across continents, hinting at a forgotten chapter of human civilization.

The Two Ninurta Statues

In ancient Mesopotamia, now modern-day Iraq and Kuwait, Ninurta was venerated as the god of war and agriculture. His visage, armed with a bow and arrow, and a mace, symbolized the dual aspects of protection and nourishment, critical to the survival and prosperity of his people.

Contrastingly, in a private collection in Ecuador, acquired from Peru by Father Carlo Crespi, stands a statue bearing a startling resemblance to Ninurta. This discovery poses a conundrum: How did two distant cultures, with no known means of contact, conceive such strikingly similar representations of the same deity?

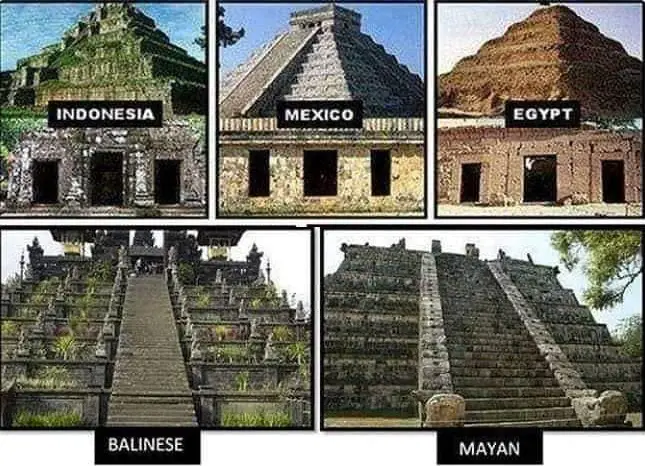

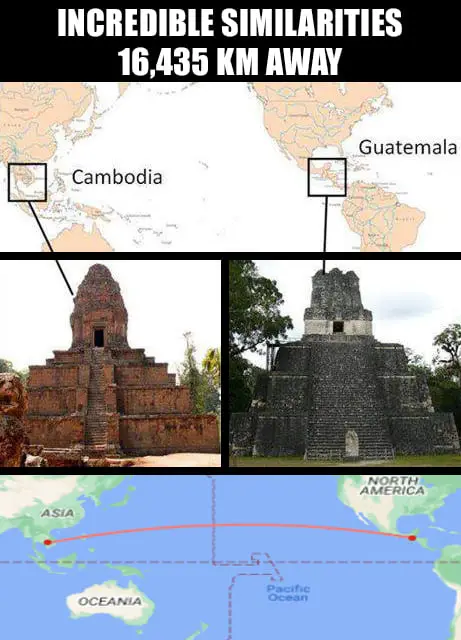

A Global Mosaic of Pyramids

This enigma extends beyond the statues to the architectural marvels known as pyramids, scattered across the globe. From the majestic pyramids of Egypt to the monumental structures in Mexico and Indonesia, these edifices share architectural elements that defy simple explanations.

The precision and scale of the Great Pyramid of Giza, the sprawling Borobudur Temple in Indonesia, and the towering Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacan, Mexico, suggest more than coincidental similarities. They hint at a sophisticated understanding of mathematics, astronomy, and engineering, shared across continents.

The Mystery of the World-Traveling Gods

The parallel between the statues of Ninurta and the ubiquitous pyramids raises a tantalizing question: Did a global civilization, worshiping shared deities and exchanging knowledge, once exist? This hypothesis challenges the conventional view of isolated civilizations developing independently.

The theory of a prehistoric “Atlantis” or “Mu” suggests that an advanced civilization could have facilitated the spread of architectural concepts, religious beliefs, and cultural practices across the world. This civilization, if real, might have been a crucible of knowledge, connecting distant peoples through a shared spiritual and intellectual heritage.

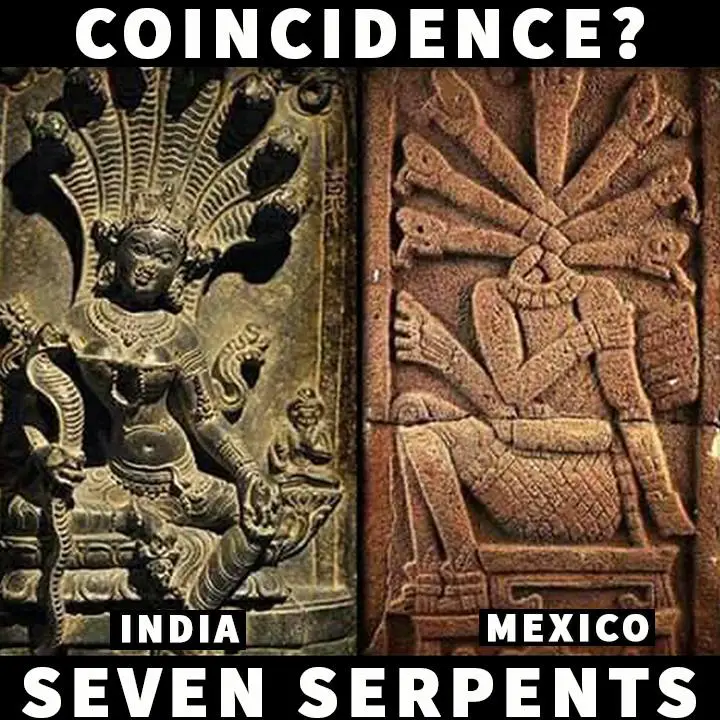

The Ancient Code of Symbols

Compellingly, the thread of commonality weaves through the symbolic language of ancient art and architecture. Serpents, suns, and celestial motifs recur in diverse cultures, possibly serving as a universal lexicon bridging peoples and continents.

The serpent deity, known as Quetzalcoatl in Mesoamerica and Kukulkan among the Maya, exemplifies this shared symbolism. Depicted as a feathered serpent, it represents wisdom and the cyclical nature of life. This motif, along with the practice of aligning buildings with celestial events, underscores a global preoccupation with the cosmos and its mysteries.

Conclusion

The echoes of Ninurta, resonating from Mesopotamia to Peru, alongside the global footprint of pyramid-like structures, beckon us to reevaluate our understanding of ancient civilizations. They suggest the existence of a once-unified global culture, rich in knowledge and spiritual wisdom, that influenced the development of disparate societies.

While the evidence remains shrouded in mystery, the similarities between distant cultures challenge us to consider a world where ancient civilizations were not isolated islands of culture but interconnected hubs in a vast network. As we continue to explore these connections, we may uncover further evidence of a shared ancient heritage, offering new insights into our collective past and reshaping our perception of human history.

VIDEO: